As part of ongoing efforts to force U.S. consumers to get rid of their natural gas appliances, a new Rocky Mountain Institute report compares costs and emissions between mixed-fuel and all-electric households in selected cities across the United States. The city-focused report nebulously presents data on both the up-front costs when buying a house and yearly utility bills in a thinly-veiled attempt to convince policy-makers that an all-electric option is not only less carbon-intensive, but also more affordable than continuing to use natural gas.

Predictably, RMI blatantly ignores a vital underlying assumption to try and demonize natural gas use. According to the U.S. Energy Information Administration, natural gas constitutes 32 percent of the U.S. total primary energy consumption and 31 percent of the U.S. electric power sector’s primary energy source. Natural gas clearly constitutes a key energy source for U.S. electricity generation.

In other words, despite RMI’s attempt to move cities away from natural gas, the economic benefit derived from an electrify-all effort will ultimately depend on affordable natural gas generation across much of the country. Dismissing this fact, however, is not only derogatory, but misleading when presenting policy-oriented reports.

Let’s take a look at some of the main flaws of the report:

RMI calculates lower utility bills in electrify-all scenarios but doesn’t recognize natural gas’ underlying role

Switching household energy systems, from mixed-fuel to all-electric, will naturally have an impact in electricity usage simply because more appliances will rely on electricity now, hence, higher electricity bills. RMI claims that this increase will be offset in savings from consumers not also having a natural gas bill.

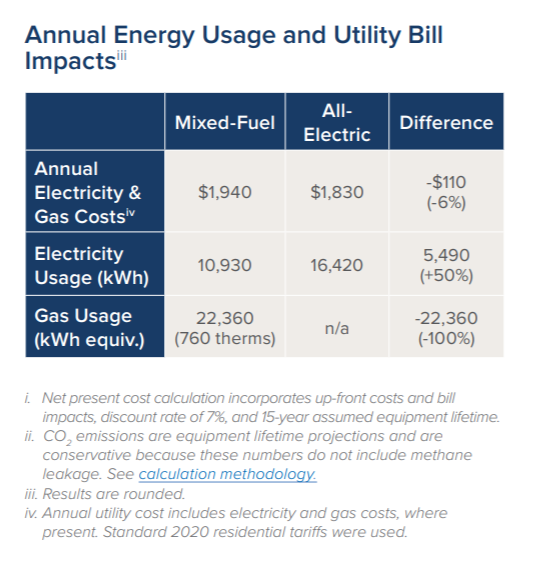

For instance, in the city-focused report on Columbus, Ohio, RMI calculates a 50 percent increase in electricity usage in all-electric cases compared to mixed-fuel buildings and a $110 average savings from this switch.

However, this argument fails to consider two main factors: a) seasonal impacts on electric’ bills, particularly in the winter; and b) natural gas’ impact on electricity prices.

Regarding the first point, according to a recent report from the EIA, households using electric heating will pay more than double this winter than households using gas-fired heating systems:

“EIA forecasts that households heating primarily with electricity will spend an average of $1,209 this winter on their electricity bills, which is 7 percent higher than the typical bill last winter.”

In comparison, U.S. households are expected to pay $572 this winter for natural gas-fired heating. This price difference is relevant when contextualizing the data, especially for the U.S. Midwest where there are three times more households using natural gas-fired heating than all-electric.

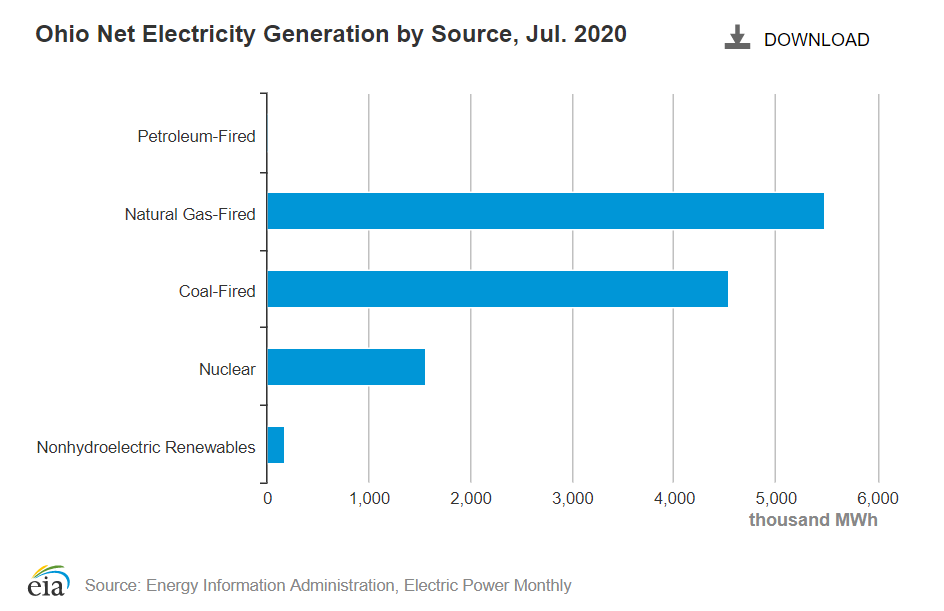

On the second point, and continuing with the case of Ohio, as the EIA graph below shows, the natural gas-abundant state heavily relies on this source for power generation:

Thus, facilitating affordable electricity prices. According to data from the EIA, as of July 2020, Ohio’s average retail price of electricity for the residential sector totals 12.09 cents/kWh, below the national average, and significantly cheaper than other states such as Connecticut (22.05 cents/kWh), Massachusetts (21.32 cents/kWh), California (20.11 cents/kWh) or New York (18.73 cents/kWh).

RMI does not take into account the added burden to the grid

The study also fails to factor into its economic analysis the fact that if the states follow a mandate or favor electrify-all regulations, as suggested by RMI, the electric grid would face significant stress from the added demand, jeopardizing the state and/or region’s energy access.

This is especially true in two of the cities RMI produced reports on: New York City and Boston.

New York City has already faced supply shortages that led to a moratorium on new natural gas hook-ups because of the state’s policies that have blocked key pipeline infrastructure. While having all-electric buildings would lessen the burden the city is currently facing on that front, it would redirect it to the grid system that is heavily dependent on natural gas.

Boston similarly relies heavily on natural gas, particularly in winter months, and also faces supply shortages that have resulted in the state burning higher-emitting traditional fuel sources to generate enough power and importing natural gas from Russia.

And both cities already face some of the highest energy costs in the country as a result.

RMI does not calculate the costs of modernizing electric infrastructure, nor the adjacent costs for vulnerable communities

Upgrades to distribution and transmission systems will be needed to facilitate an all-electric future. These improvements take time to build, are costly, and face permitting challenges.

This is already a pending issue for utilities and policy makers in the United States. For instance, according to the latest report on electric infrastructure from the American Society for Civil Engineers (ASCE):

“The total gap indicates that the U.S. is facing a $208 billion (in 2019 dollars) shortfall by 2029 and a $338 billion shortfall by 2039 in what is needed to ensure a reliable energy system.”

What’s more, ASCE also warns that failure to revamp or modernize electric infrastructure will represent significant costs to households:

“[L]ost disposable income is projected at $13 per household per year in 2020 but will grow to $563 by 2039 if the generation, transmission, and distribution investment gaps are not mitigated.”

However, RMI fails to consider these costs implied in modernizing both the grid and the transmission lines, which ultimately will be socialized and added to all U.S. resident’s monthly energy bills. In addition, relying on all renewable-energy powered electricity will bring about additional costs, such as transmission investments to bring solar and wind energy to where the load is, such as urban areas.

A final thought about the actual implementation of these electrify-all programs, land costs and housing costs also vary significantly from state and city. Certainly, living standards and salaries in New York City or Los Angeles drastically dwarf those in Columbus, Ohio, for example.

But appliances costs don’t vary much in general. In fact, a relevant factor that RMI should be integrating in its electrify-all reports is whether the adjacent and peripheral costs of electrification can be absorbed by lower-income families, vulnerable or rural communities.

Taking into account the current economic situation in our country, where many are struggling to make ends meet – these policies will not help them in any way. In fact, the energy burden will only grow larger. Instead, it seems policymakers should be focused on how to use safe, affordable, and low-carbon natural gas to ensure that people don’t have to make a choice between staying warm and putting food on their table.

Again, RMI advocates for policies that would not help Americans, but harm them.

This post appeared first on Energy In Depth.